ASCHOY //

Asociacion Chojcha de la Hoyada

Documentation ASCHOY projects 2007 - 2014

Aschoy was founded in 2007 in the city of La Paz-Bolivia. ASCHOY is a collective group that researches and produces various forms of art from the standpoint of popular culture as the source for a horizontal dialogue on the process and the creation of arts. The collective activates and participates with various groups like shoe shiners, hairdressers, embroiderers, musical bands, music instrument makers, street photographers, artisans, couturieres, prisoners, day laborers, to collectively create art manifestations. ASCHOY assimilates the “CHOJCHO” aesthetic as a genuine and original “avant garde “ manifestation, that is the result of the social and cultural clashing between the original culture confronting the western dominant culture, “CHOJCHO” then becomes a syncretic expression that embraces a range of manifestations. This aesthetic is particularly visible in the city of La PAZ- Bolivia.

The following pieces are produced in collaboration and under those premises, creating a dialogue with a common language about the syncretic experience in this city.

The following series are part of a larger sitespecific project that is a result of recognizing the multiplicity and variety of elements that create the dense local aesthetic and popular culture. A series of pieces were created with embroidery artisans, another with carnival artisans, a performance was executed with shoe shiners, and a series of photographs were made with day laborers in collaboration with a street photographer.

The result had a community impact. The local television registered the street performances. As a result the shoe shiners were invited to talk shows to talk about their reality. As a result of my research on “Chojcha aesthetic”, I developed a series of pieces that portray that aesthetic experience. These pieces are a synthesis of my experience as an artist and researcher.

Chola Aesthetic

The Chola (also known as Cholo) are people of mixed Spanish and Native American origin. The Chola aesthetic is a clear manifestation of a marginalized society that was forced to copy European canons imposed during colonial times. In brief, the Chola aesthetic is a mix between occidental influences with indigenous features that is particularly apparent in the city of La Paz, Bolivia. Through the frame of multiple influences that come with modernity and consonant global processes, La Paz Bolivia has the indigenous and mestizo as the main protagonist of the urban and architectonic unequilibrium embedded in its urban structures. This new protagonist has created an architecture and further an aesthetic of intermixed and exaggerated features that started to germinate in a section of the city where small commerce and the new bourgeoisie concentrated. In this way the chola-mestiza aesthetic permanently consecrated spaces of entrepreneurial cultural dialogue that resurfaces as a baroque manifestation and functions as anti-elite expression of the sublime ideas of the mestizo criollo.

Research Projects Example

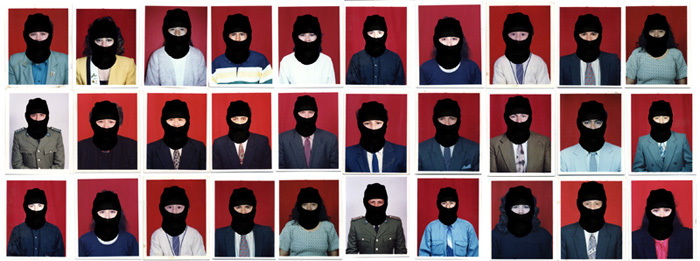

Project 1 / The Mask of the Shoeshiner

The mask of the shoe-shiner

The mask can be seen playing several roles in the Andes region: in rituals, at carnival; but also as a manifestation in the social-political fabric. The mask of the shoe-shiners in La Paz, Bolivia is particularly distinctive. Since the economic debacle of the mid 1980’s, caused by the drop in price of the major export of that country—tin, the young professionals left their houses in desperation to work on the streets, many of them as shoe-shiners. Because this unspecialized labor was seen as a lower-class occupation, they covered their faces.

As Roberta and Peter Markman state in their book “Masks of the Spirit”: “. . . the mask simultaneously conceals and reveals the innermost spiritual force of life itself. Precisely this fundamental opposition of the two ways in which the mask symbolizes the essential relationship between matter and spirit (Markman and Markman 1990: xix).” The mask plays with this duality, in the case of the shoeshiners, hiding their identity so they can function in society without any link to their daily activities, but revealing a fragile socio-economic fabric, where the mask becomes their protection against exclusion and discrimination. They also cover their faces with the mask because this type of labor is socially discriminated against by their peers. The mask becomes a symbolic expression of an in-transit fragmented identity that allows them to resist the economic debacle, where they don’t perform any agency. The mask reveals a society that segregates and excludes by hiding their persona.

Collaboration with Don Apollinar,

street Photographer and day workers Mercado Yungas,

La Paz - Bolivia.

Mr. Apolinar Escobar is the last street photographer using analog photography in the city of La Paz-Bolivia, when I met him in 2010. He stands in the small plaza of Alonso de Mendoza, a place that he has occupied for more than 30 years. He is surrounded by other identity card portrait photographers, whom exchanged their analog cameras for digital while keeping the façade of the analog era.

Mr. Escobar takes photos using a German Tessar 1250 camera. This camera, also known as the “minute camera,” is a self-sufficient unit that allows the photographer to produce a paper negative and develop the image inside the camera, producing a black and white image.

As a direct consequence of the manual process the result of the paper negative varies over time. The fixing--the process that stabilizes the image by removing the unexposed silver halide, is responsible for the continuous oxidation of the image. The paper negatives appear to be in continuous process manifesting its unstable condition. The negatives continue changing, as a concequence the images will disappear in the next couple of years.

Portraits in the Yungas’ market. / La Paz, Bolivia

This series of photographs find reference in the image “the Giant of Paruro”, by the Peruvian photographer Martin Chambi. Chambi’s images, taken around 1925, became an iconographic image of the Andes region, as Chambi documented the social fabric while acting as a social commentator.

The Yungas’ market, in La Paz, Bolivia, has become the place for day laborers to wait for patrons. They stand at the edge of the street. Placed on the floor next to each one is a bag with a label briefly describing the type of labor that they perform: plumber, electrician, carpenter, etc… For this series I collaborated with Mr. Apolinar Escobar, a street photographer, who is one of the last in the city of La Paz to take photos using a portable processing of paper negatives* using a German Tessar lens. For this series we created an improvised studio in a parking lot and we asked the day laborers to pose for the camera in our ‘studio'.

-------

* Using photographic printing paper the photographer would expose a sheet of paper for the negative, develop, stop, and fix it inside the camera, then put a copy stand on the camera and photograph the negative (to obtain a positive), develop, stop, and fix, then wash the final print in a can of water attached to his tripod. The camera was advertised as “One Minute Photo Postcards”.

Whitening Identities

Through applying red ink to the negative, the photographer makes the image lighter in tone. In this case, the photographer modifies the color of the faces of clients who ask him to, making them appear whiter. Fanon argues that colonized subjects internalize an inferiority complex induced by colonizers, which the colonized attempt to mediate by appropriating or emulating the culture of the colonizer—including appearance. Some clients consequently choose to modify their images to reflect an appearance more similar to the dominant perception of positive western attributes.

Process of “One Minute PhotoPostcards.”

Using photographic printing paper the photographer would expose a sheet of paper to obtain a negative image, the entire process involves developing, stopping, and fixing the image inside the camera itself, protected by a fabric that covers the photographer to insulate the process. During the process of negative creation, the image can be manipulated to change tonalities. In that context brushing the negative with red ink provides a filter to obtain a lighter tonality on the skin. The negative is then placed on a stand in front of the camera and photographed (to obtain a positive), developed, stopped, and fixed, and then the final print is washed in a can of water attached to the tripod.

The following series are part of a larger site-specific project that is a result of recognizing the multiplicity and variety of elements that create the dense local aesthetic and popular culture in Bolivia (denominated “Chojcha aesthetic”). A series of pieces were created with embroidery artisans, another with carnival artisans, a performance was executed with shoe shiners, and a series of photographs were made with day laborers in collaboration with a street photographer.

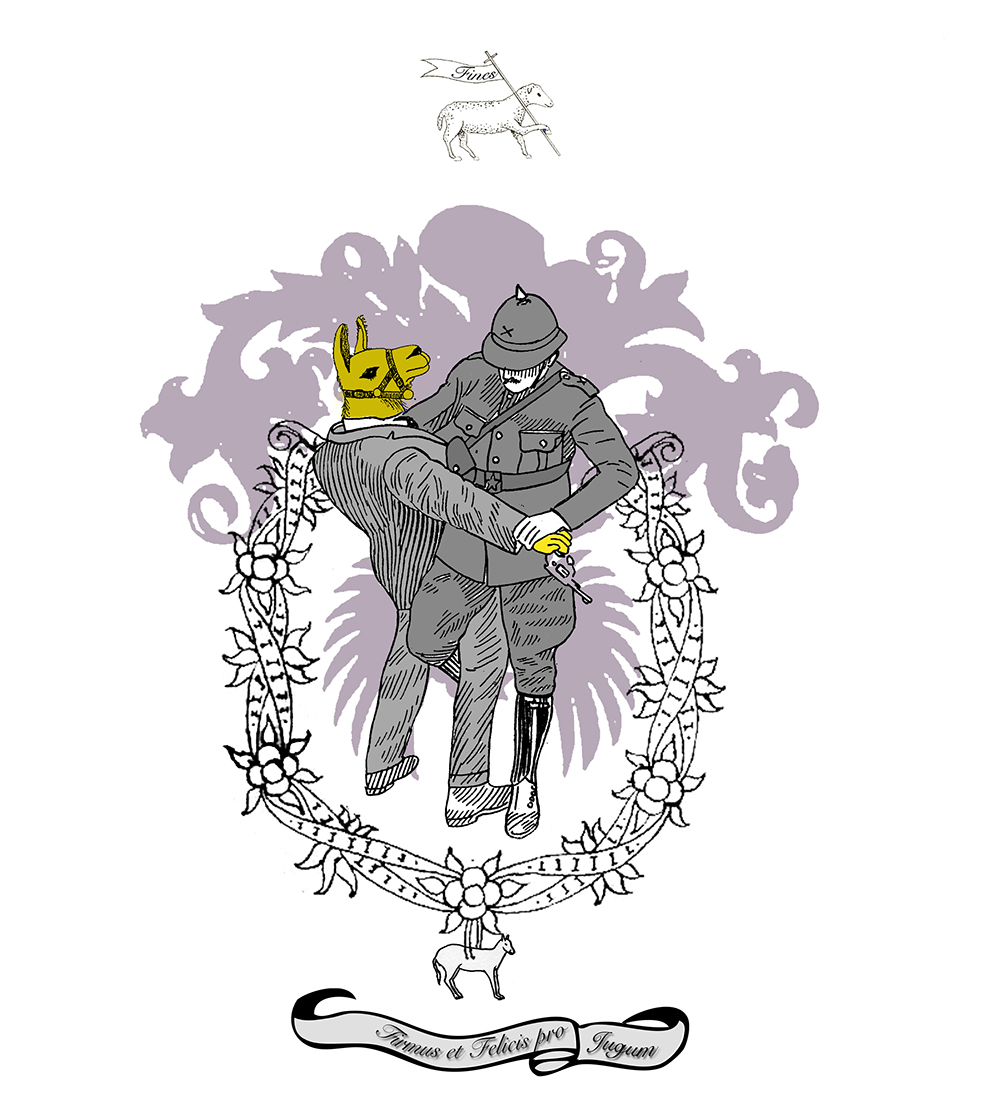

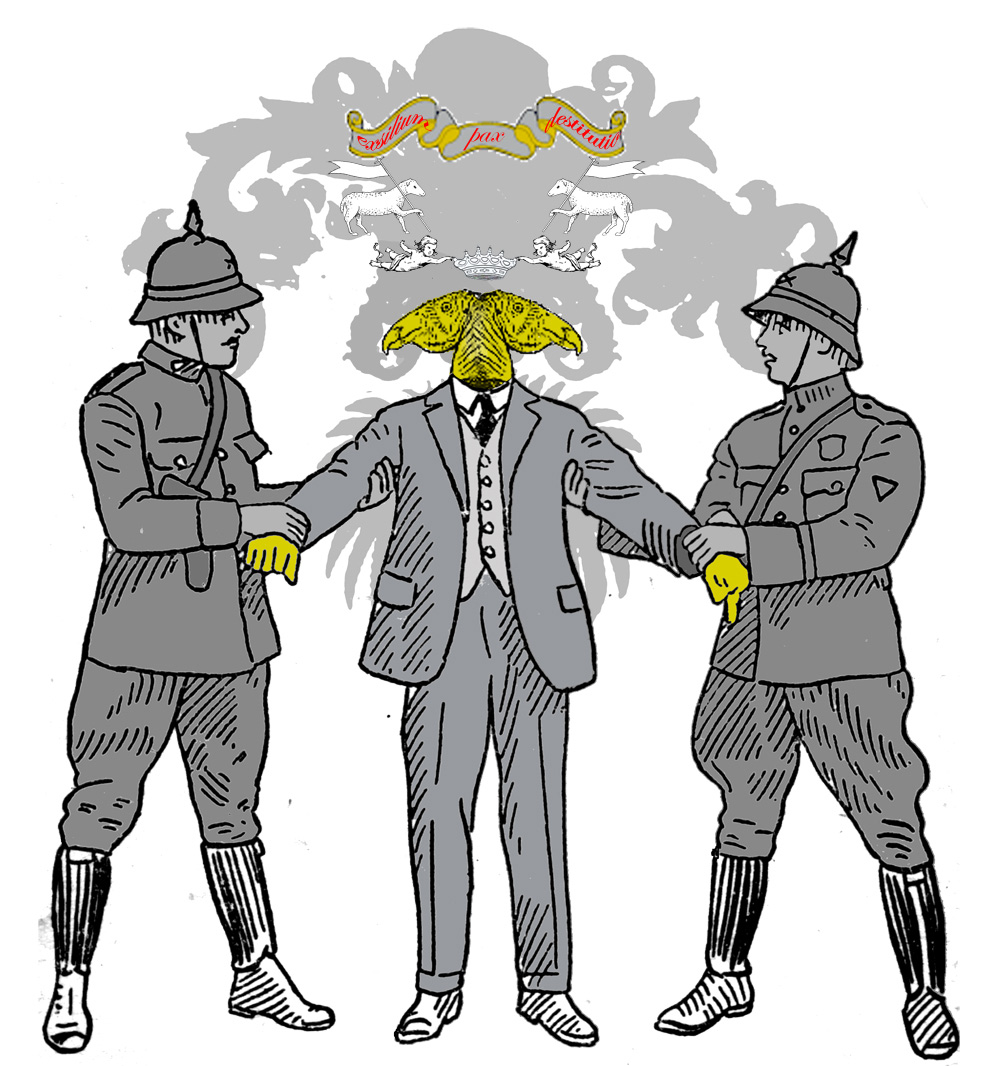

Centropia / research on Latinoamerican imaginary

Centropia is a social response project that is adaptable to the context where it takes place. It is an illusionary new center for an utopian social fabric. Centropia, is an ever-evolving series of art actions; art inserted into the quotidian, relational art, community art, an art that is based in the vocabulary of the urban landscape in Latin America.

Found manual, distributed to the Chilean police (1960-70)

This project adopts various vocabularies, formally and conceptually influenced by the “mestizo-baroque” art spread throughout Latin America.

Centropia, has different thematic units, each focusing on diverse techniques and subject matter, from militarism and religion to social unrest and social exclusion.

Centropia 01 is a project that takes my vision of South American superstructure—militarism as a patriarchal power, religion as a colonial representation, and excess that is represented as baroque, and ultimately as madness—as a starting point. With this trilogy, I created this piece that centers on a book that I found on the street in Santiago, Chile. This book was written in the 1960s and teaches police how to control thieves. A series of images are made subtracting the thief and replacing him with native Latin American animals. Flags were embroidered portraying these images in the same style as imagery embroidered for Catholic processions. Six monitors animate the struggle engaged in by these combatants.