The Things We Lost in the Fire

Is a multilayered project initiated by a family event in southern Chile. It explores fire and home as transformation, memory, and demise symbols.

The Things We Lost in the Fire was also a project that expanded into the COVID-19 years in a collective effort with the Icebox collective to facilitate public conversations about the changes and moments of mourning during those years.

The Things We Lost in the Fire / Story

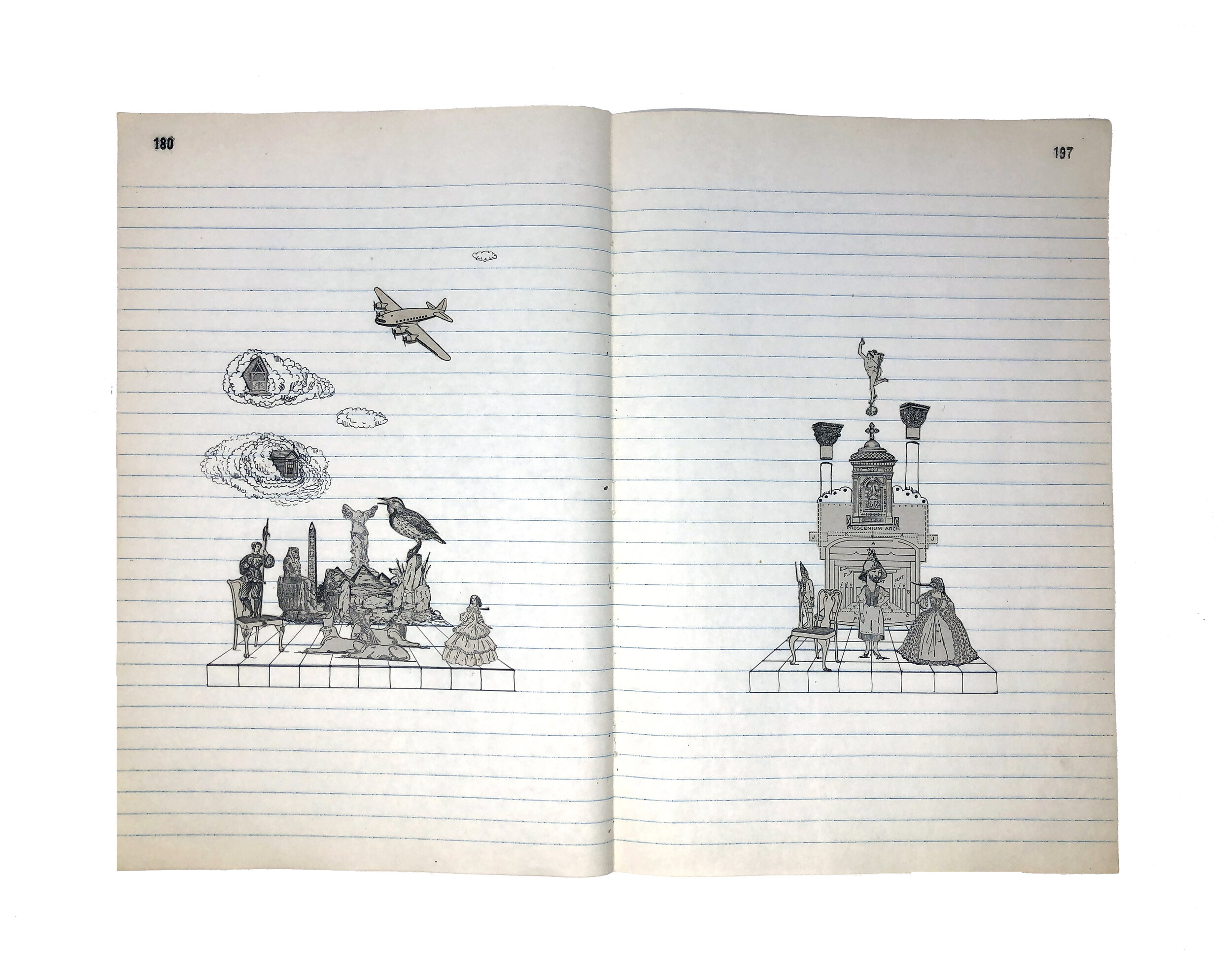

The fire had carried away everything that existed between those walls. Without waiting for witnesses, the flames appropriated the memories in penance in that small house. They intruded, taking charge of objects thought to be immortal, and turning them into gray earth, burnt ground, smoke and stench.

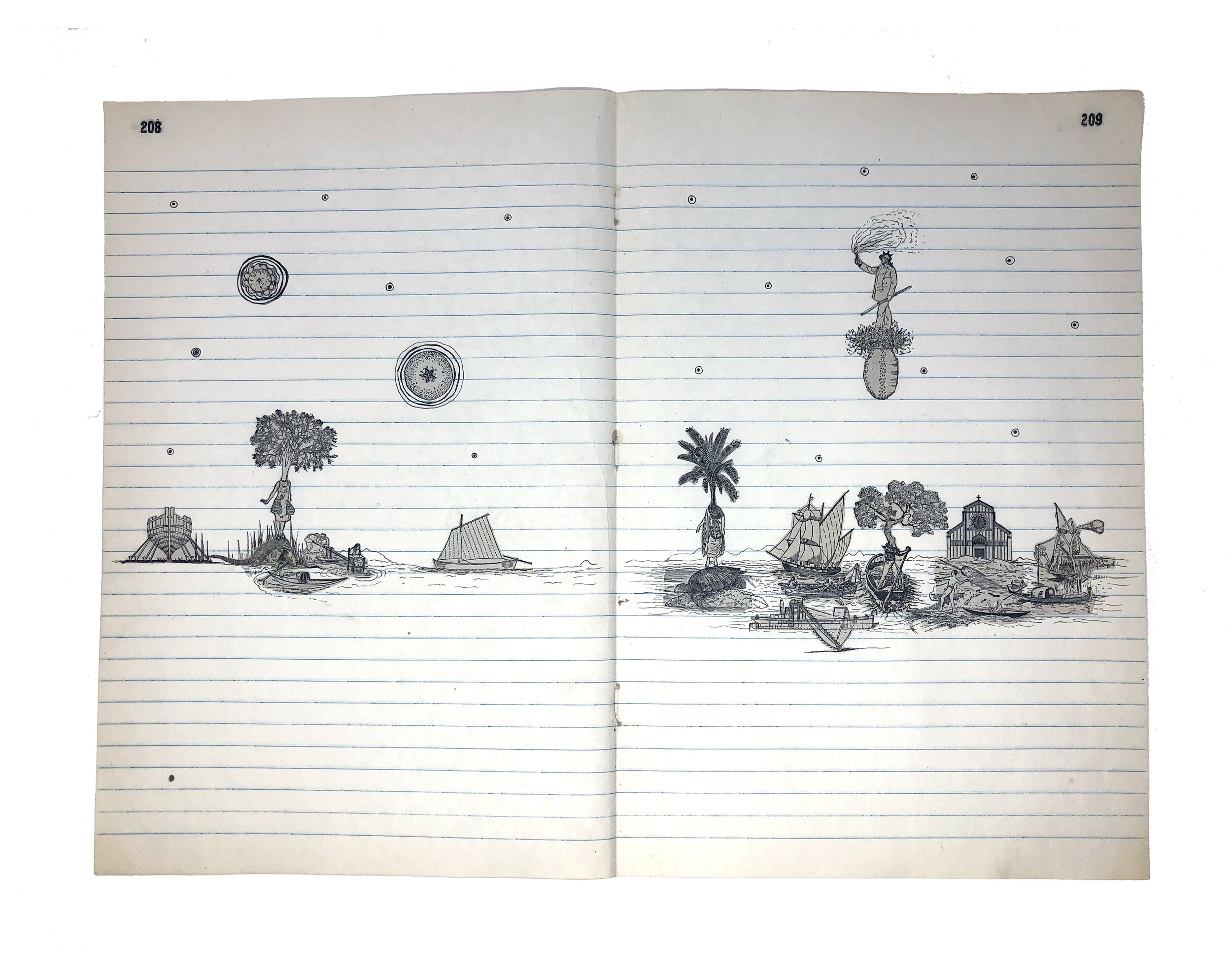

It was a modest little wooden house among some old cherry trees, where the thin walls served as dividers to signify the impossibility of privacy, which no one really wanted in the end. It was a house conceived in an informal way, like a shelter to that violent cold that springs up with slow winters, that rainy south, and dull nights.

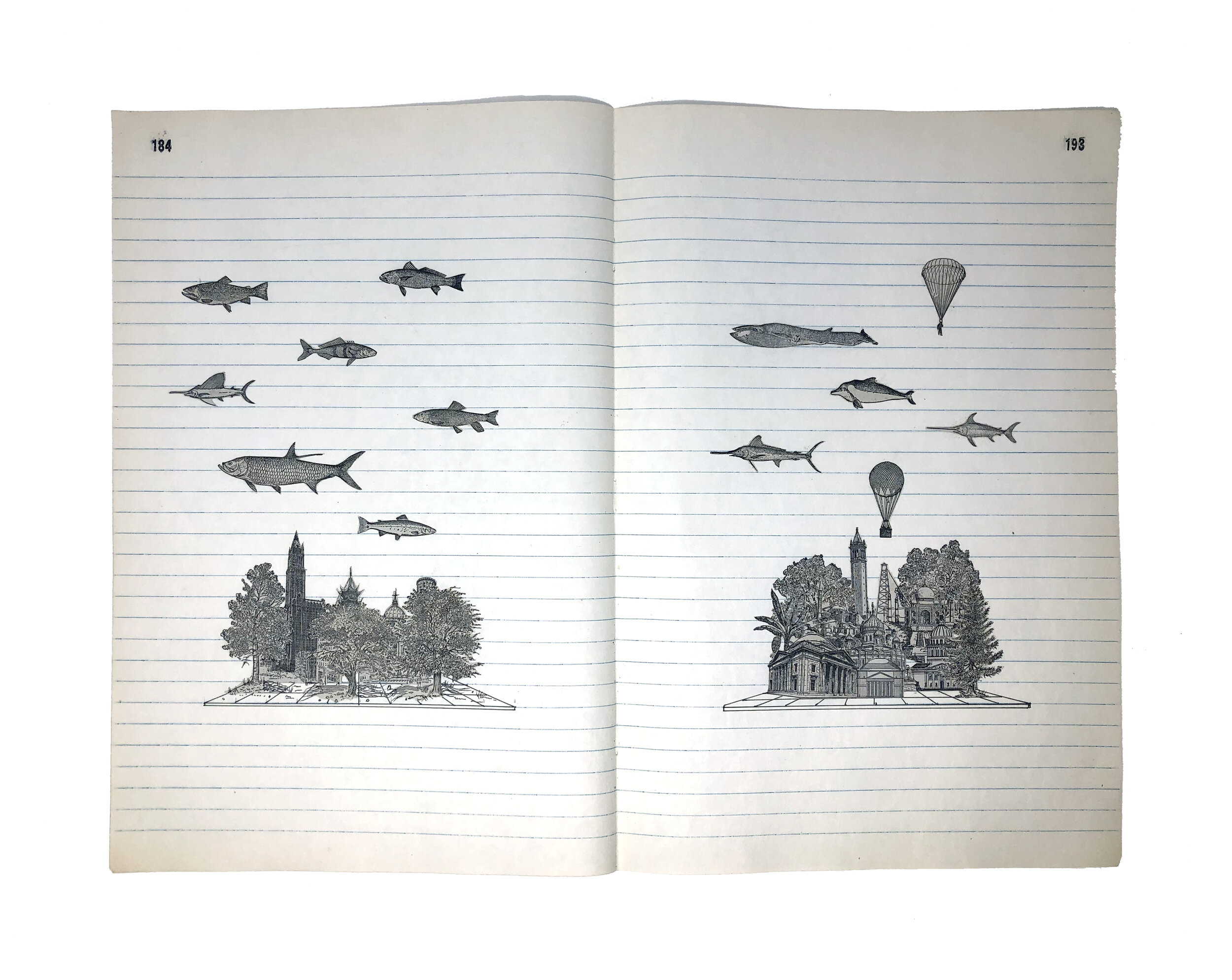

That small house was never thought to be everlasting—it was a house that was imagined as a refuge for a given moment—but against the house's will, the shelter was transformed into a home, and it slowly adapted to the times, to its occupants, to its winters. So those occupants and time started to leave marks, plugged holes, and leaks appeared in the walls, moving furniture and stacking calendars, leaving reminders of time like any other house. The small, outdated, and austere house easily captured the heat of the fragile wood fire stove; the modest house always managed to receive its occupants with a hug.

A few meters from the small house, a new house began to be built. One that reflected the ideals and aspirations of the future occupants, the new great house that—like an ark—would save their occupants from those flood winters, from confined spaces, from paper-thin walls.

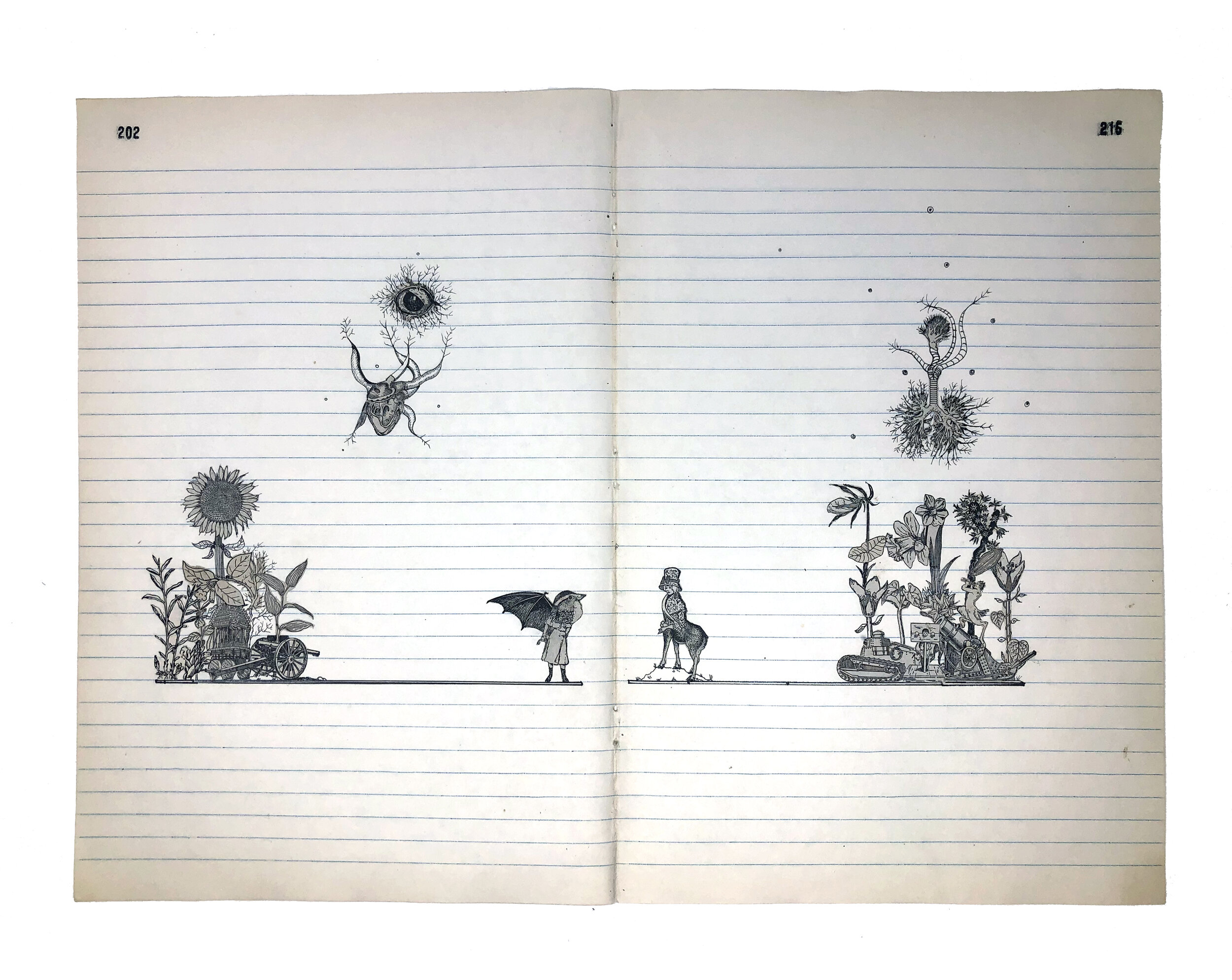

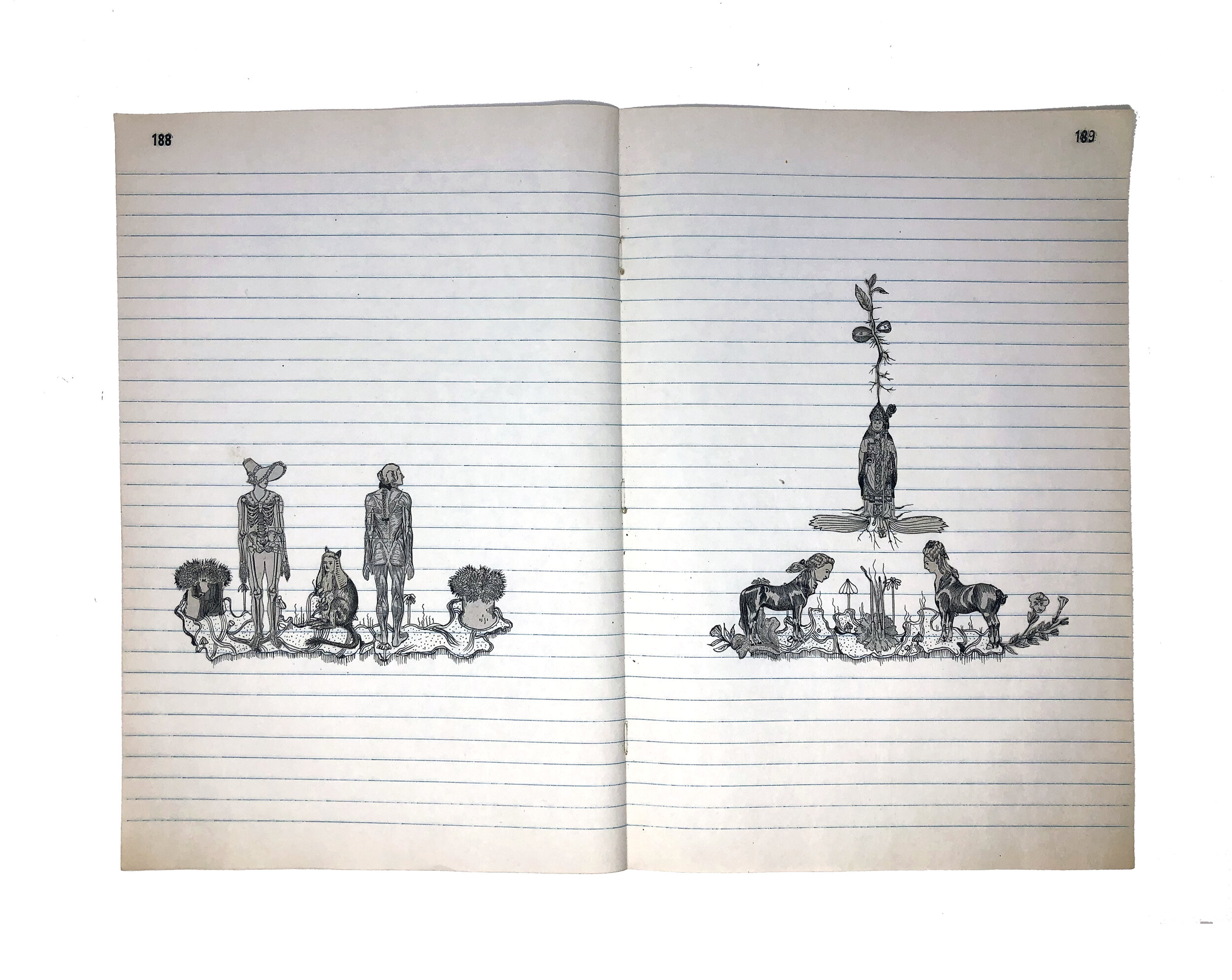

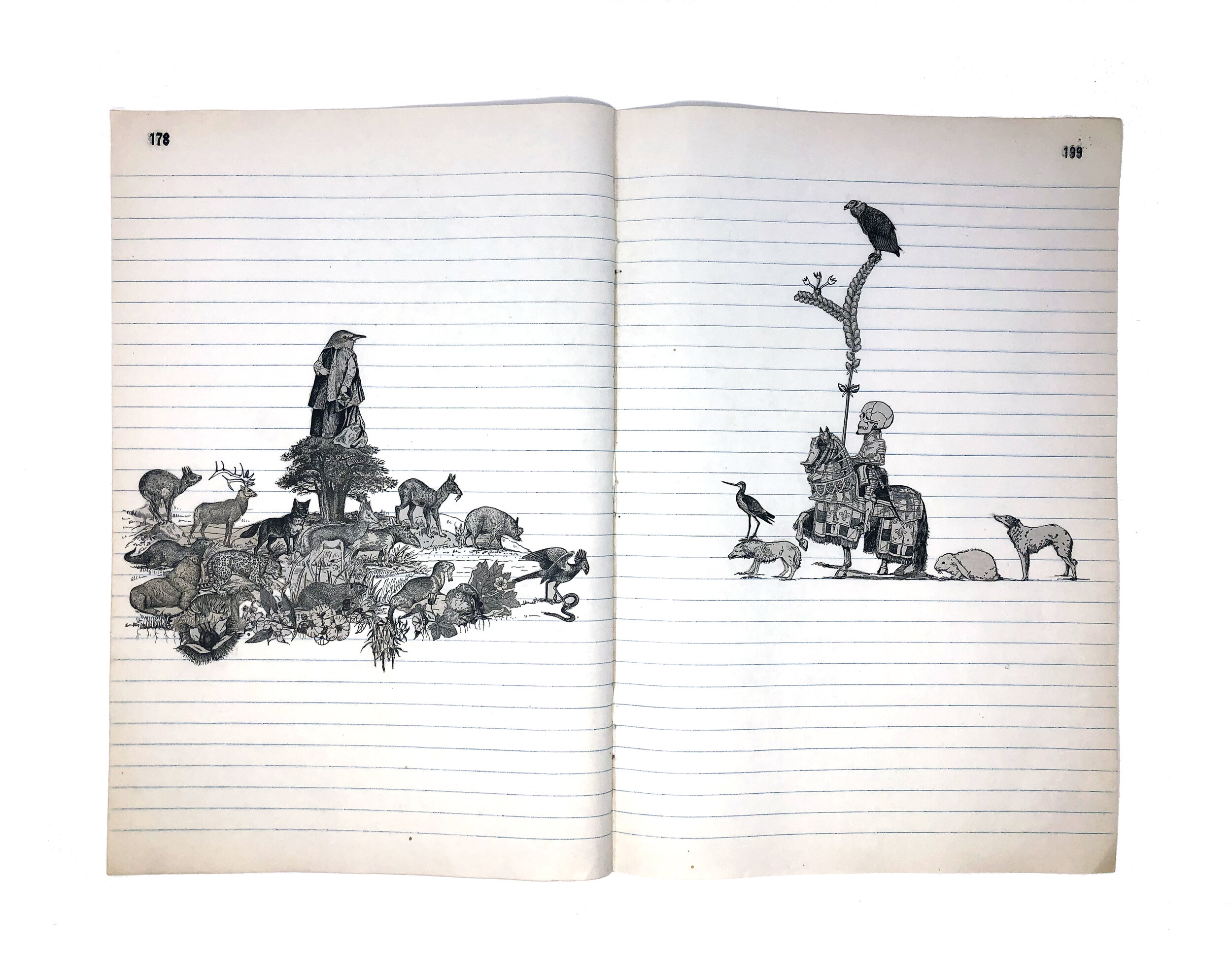

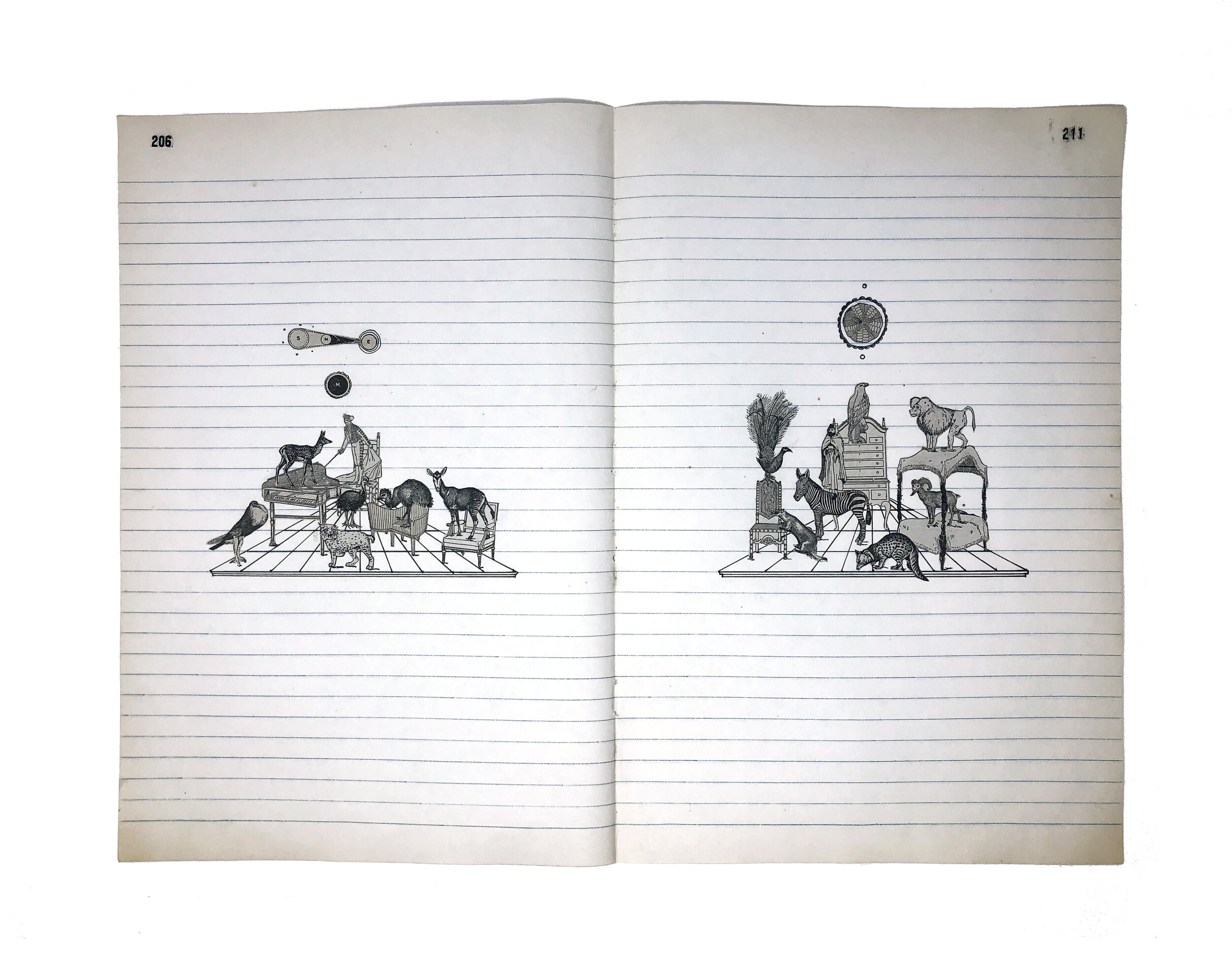

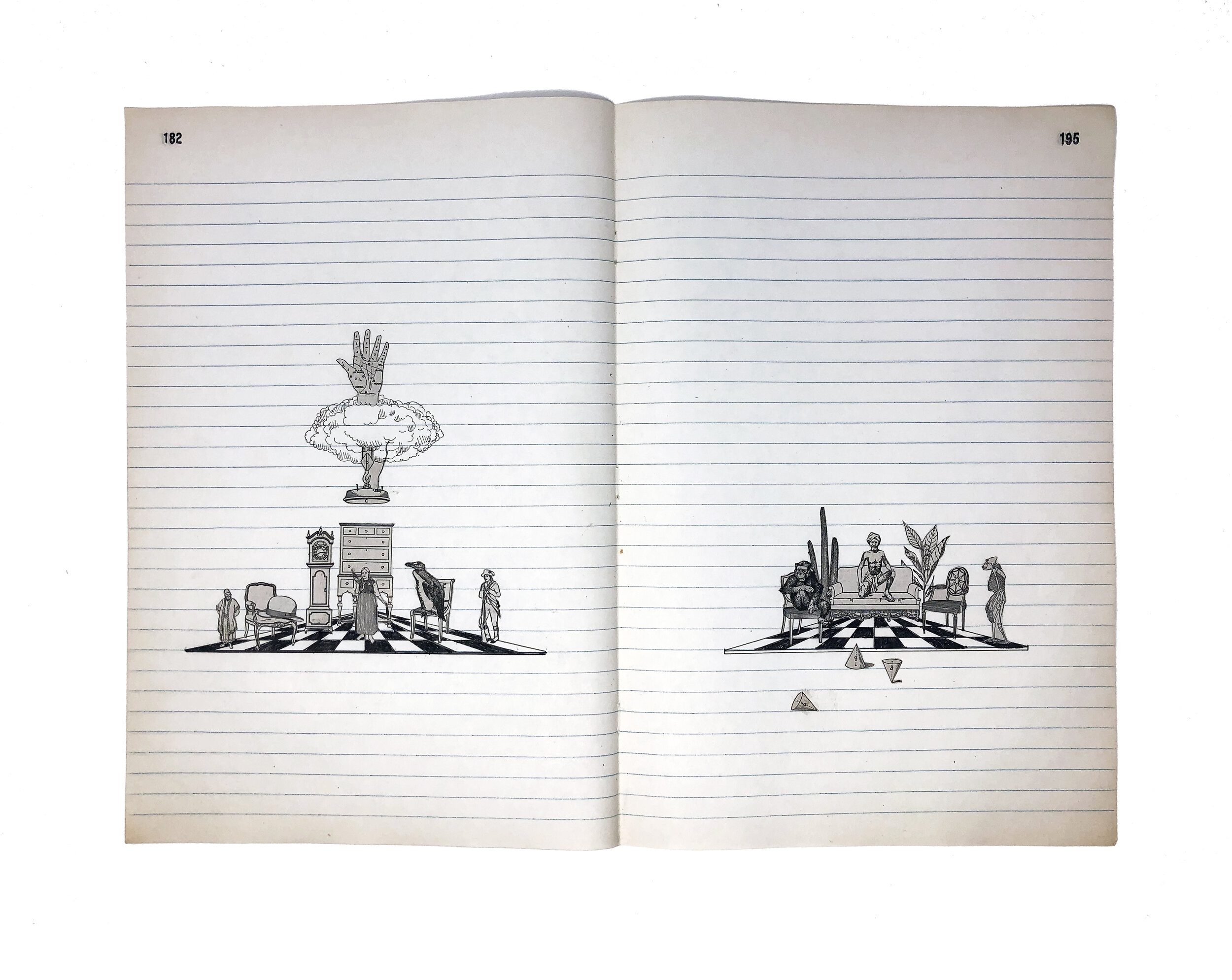

As the great new house came into being, without explanation or ceremony, the little house was transformed into a repository, a kind of cemetery of furniture, archives of unclassifiable documents, books without covers, limp chairs, and damp clothing. Then the little house - which at some point before was a chicken coop - accepted its darkness and abandonment and, without being consulted, became a refuge for rodents and insects. It shrunk from winter to winter as the wood was unleashed by the wind. The small house looked askance at the big house that was being hammered into shape, a huge house that looked more like a ship left by mistake in a mountain. The small house became damper; grass grew between its wounds, the glass windows were covered by plastic to contain the rain, and its exterior walls took the yellow of the obligatory moss of the south.

That day in November, early spring, the small austere house could no longer handle the negligence and abandonment, and it caught fire, as if in warning or protest, about the dispossession of grievance and departure. The neighbors who arrived - invited by the fire that rose with pagan fervor - thought of the possessions. The former occupants, undaunted in front of the fire, thought of the memories of the stripes with the marks of the children's heights in the framework of the door, of the nails in the wall that served as hooks for the pots, of the crocheted fabrics that hid the holes in the furniture. Its occupants looked at themselves and were fragile, subdued by the fire that consumed their memories. That cold November day, the small house, austere but with monumental stories, became a deadly artifact, revealed by the fire to be temporary and ephemeral.

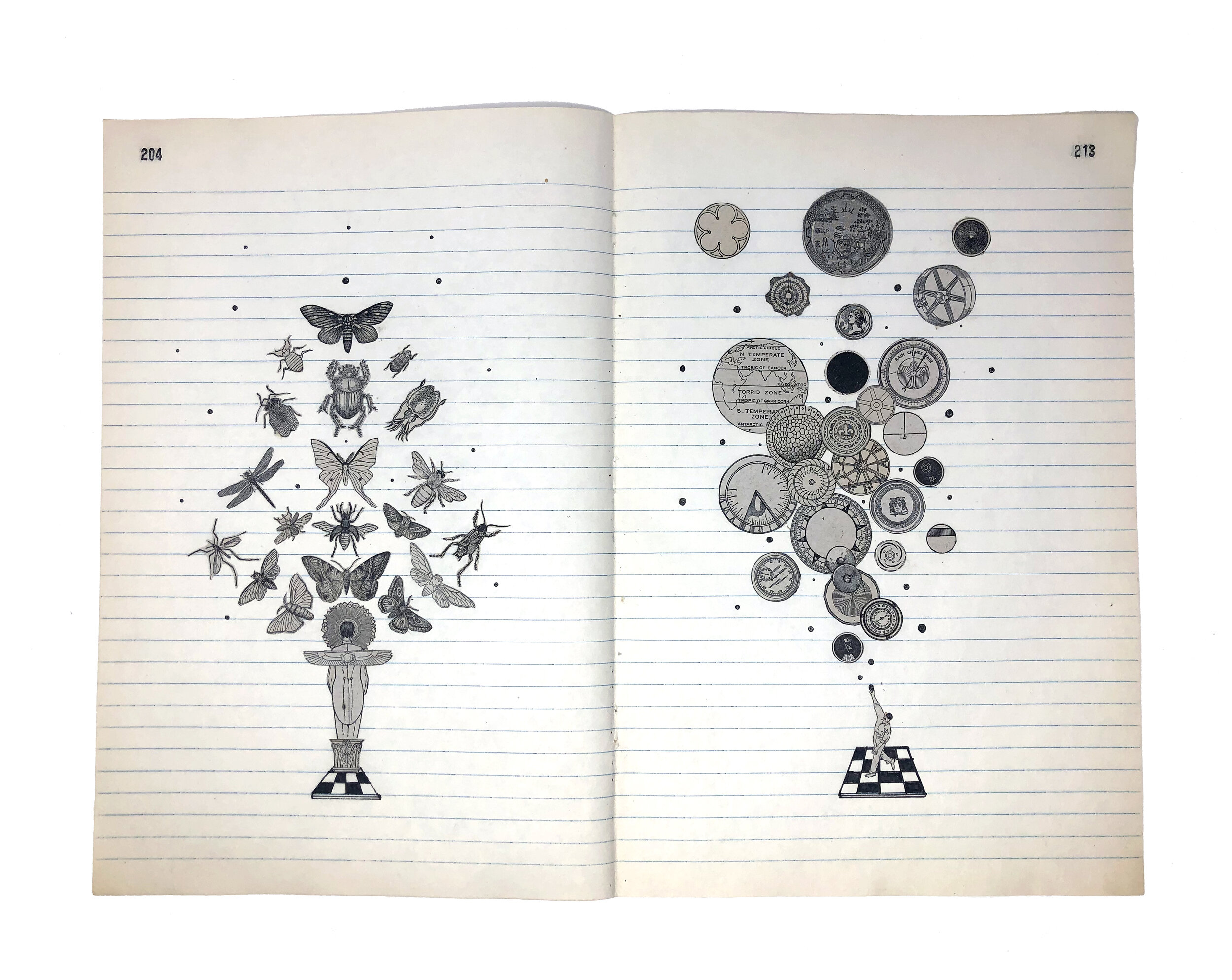

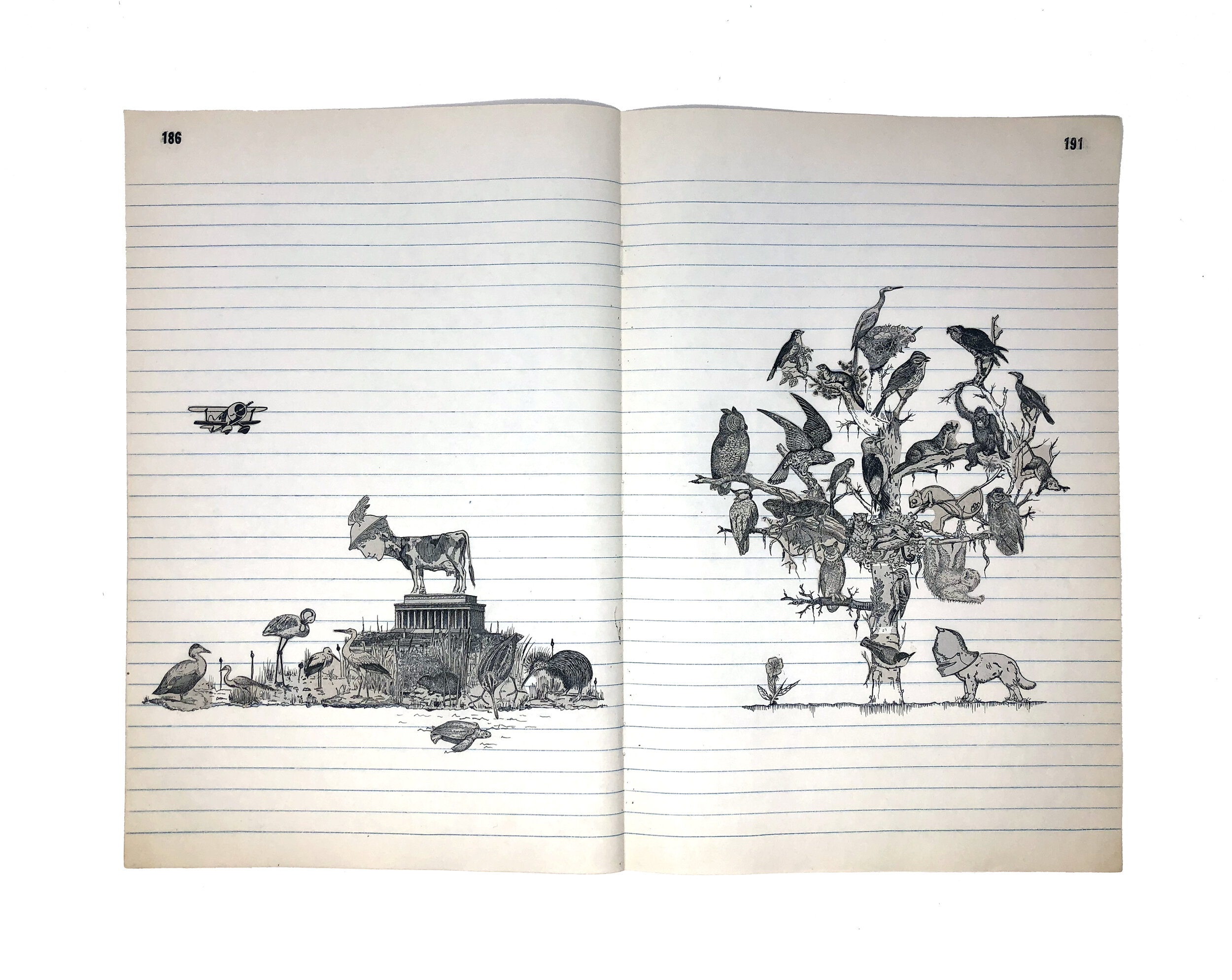

There were many stories of that fire but few heroes. There is only the oral testimony that Don Edgardo Endress Stollsteiner, owner of the house, in a futile act, entered the burning structure to leave with a bound book, in which, at some point in the remote past, he had kept some accounts. The red book read on its spine: 'Republic of Chile - Fiscal Office.' With it, he had also taken a Larousse French-to-Spanish dictionary with a green cover dictionary.

Six months later, the burnt smell did not disturb the memories so much, and the vacant space that became the house had once again become a chicken coop. That May morning, inside the new colossal house that seemed like a vast and unoccupied territory, Doña Gabriela Bórquez Miranda, owner of the house and wife of Don Edgardo Endress, fell for the second time. But that second time, she did not stand again and, lying on the cold wooden floor, said goodbye to everyone and everything and felt how her breath and her warmth fled. For that moment, there was only one witness, Don Edgardo Endress Stollsteiner, who, without crying yet, picked her up and placed her on the bed, thinking about all the things that were lost in the fire.

The things that we lost in the fire

————————————

Ledger Records