BonDieuBon Project

a collabotive project with Lori Lee

:: Preface // Bon Dieu Bon

Text written as part of the Creative Capital Grant

by :: Luis Francia

An abandoned backpack found on a beach in St. John, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands, provides both material and inspiration for Edgar Endress and Lori Lee’s Creative Capital video project, Carry On. Discovered on shore not far from a 2002 dig in which Lee, an anthropological archaeologist, was involved, the backpack had belonged to a young Haitian man seeking a better life in the U.S. It contained an assortment of personal items, from correspondence and clothing to toiletries and audiotapes. The pack’s owner was part of a continuous stream of migrants who use the U.S. Virgin Islands as a jumping-off point. “People would swim to shore and change their wet clothes,” Endress says, leaving behind the things they’d brought with them on the journey. Endress and Lee started to collect these items and photograph them. They learned that such possessions were deliberately discarded by illegal immigrants from as far away as China and as close as Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Casting off items from the “old world,” as it were, meant the voyager could travel more easily. At the same time, this act of abandonment resonated with the symbolism of starting afresh. Endress is himself an immigrant—from Chile—and at the time of the backpack’s discovery, his own status was uncertain, as his application for permanent-residency status was still being processed. (It’s since been approved.) He understands what it’s like to stand at the margins of society, and to reconfigure one’s identity so as to fit in. On St. John, for instance, while Lee worked as an archaeologist, Endress labored as a house painter alongside undocumented persons. He and Lee hope to find the backpack’s owner—whom they have aptly named Ulysses—wherever he may be in the Haitian diaspora, and to return his belongings to him. It’s a near-impossible task, but the two are undaunted. To contextualize his identity and uncover some leads, Endress is planning a trip to Ulysses’ home town in southern Haiti in early 2006. Due to that country’s near-anarchic conditions following the ouster of President Aristide, the trip is fraught with risk. But Endress regards Ulysses as a potential collaborator, stressing that it’s crucial to ask his permission to use his material. If the pack’s owner can’t be found, or refuses permission to document his migratory life, Endress and Lee will fictionalize the events. But the fictionalization, Endress emphasizes, “will happen over there, on the spot”—a kind of cinema vérité, inspired in part by the work of innovative documentarians Jean Rouch and Juan Downey, who use alternative approaches to narration and the task of “framing the ‘other.’” Whatever mode Endress and Lee adopt, the video will be “about the process of humans moving through different sites, about reconstructing a person’s identity.” As Endress puts it, people tend “to simplify migration as a unilateral issue, as simply a matter of economics. Haiti, for instance, has a weird status” in terms of U.S. immigration policy. “Sometimes Haitians can come as economic refugees, sometimes not. And of course, there is racism involved.” Not to mention ideology: refugees from Castro’s Cuba, for example, face no such legal ambivalence. Endress and Lee have been working together creatively since 2001 when they began this project. The combination of their different vantage points (scientific and artistic) provides this project with multiple layers of meaning. Endress explored similar themes in his 2005 installation, Passage, at the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, Germany. The installation involved a video projector, 17 slide projectors, 1,360 slides, and 170 still images—what he describes as “a collective manifestation” of one of the enduring phenomena of our times: the mass movement of people globally. Through Carry On, Endress and Lee hope to further the understanding of illegal immigration and its significance in our lives, this time by giving it an individual face.

BonDieuBon / Research on migration

“Bon Dieu Bon” (God is Good), is a term used in Haiti to express the hope that even under the present circumstances a person can find a solution to the specific problem(s) that affect him in that specific moment. Although “Bon Dieu Bon” could be perceived as solely an expression of people’s hopes it is simultaneously an act of submission to the circumstances, implying an external solution to the concrete problem; the solution is exogenous. The original project “Bon Dieu Bon” is centered on the process of immigration to the US Virgins Islands, but the project also includes the historic and social contexts of Haiti and the relations between Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Immigration to the Virgin Islands. Immigrants enter the islands at night in areas less illuminated by artificial light. They swim to the shore, performing the last action of a journey that led them through a series of islands in the Caribbean. Hiding behind bushes, the immigrants find themselves wet, fearful, and disoriented. In that state they abandon, forget, or lose clothing, letters, photographs, and other objects. With the break of daylight they will take predetermined paths searching for a public phone, information, or sometimes a face that looks familiar, the face of another immigrant to obtain some orientation and hopefully support.

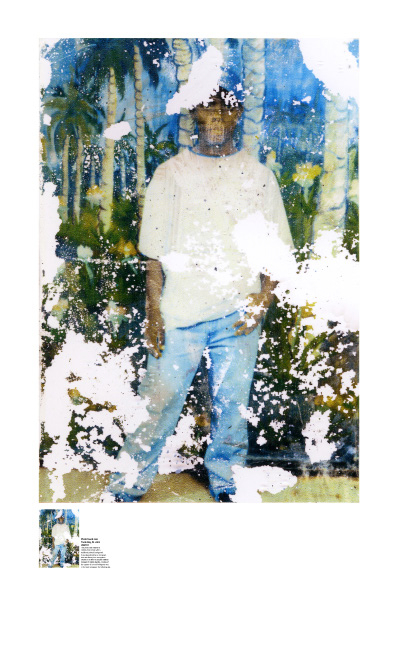

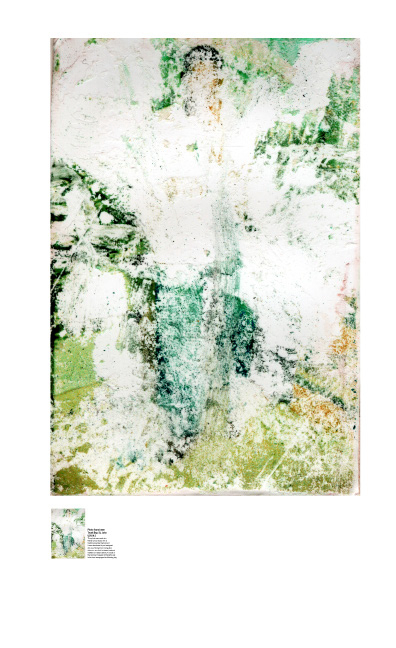

The objects left by the immigrants are the source for an archive about transit, physical movement, and simultaneously about social movements in the Caribbean; these stories are narrated though material culture. Elements that repeat in the archive are the portrait photographs, found in wooded areas, near the shore or on the side of trails. These images are the markers of the migratory process and the transformation that the immigrants and the photographs suffer together during the migratory process due to the exposure to natural agents like the salt, the water, the rain, the sun, etc. The portraits become witnesses of the physical and psychological effects of the trip; a metaphor of an identity in transformation.

Carry On: The Backpack. The archive contains an abandoned backpack found in the US Virgin Islands, belonging to a Haitian immigrant containing 18 groups of articles. From the beginning the idea was to return it to the owner, that search led us several times to Haiti.

Each object of the backpack was individualized, archived and numbered to create an archive. An attempt was made to recreate the context, analyze the origins and to investigate the symbolic aspects and potential meanings of each object, where the result is expressed in visual, written or audio form. The purpose of this re-contextualization is to broaden the reflection about the relation of the material culture to Haitian realities and the Diaspora. Research into complex social historical aspects such as politics, race, and economics were integral to this process. The archive abandons its passivity in attempting not only to situate the peoples’ movement but reflect on larger historical processes of exclusion, disenfranchisement, and disempowerment. Part of the project “ Carry On” in search of Ulysses. / Aquin - Haiti

BonDieuBon/ BDB::BP::004

Single page found in the backpack.

a collaborative project with anthropologist Lori Lee

and artist Joseph Casseus

BonDieuBon / a journey through suspension.

Bon Dieu Bon (good God good), is a term used widely in Haiti to express hope that despite the present circumstances, somehow things will work out. Bon Dieu Bon is an ongoing collaborative project with Lori Lee, an anthropologist. The original project focused on Haitian emigration to the Virgin Islands and it has progressed to include issues in the Haitian homeland and migration to the Dominican Republic.

Immigrants land late at night in areas less exposed to artificial light. They swim to the shore, performing the last stroke of a journey that goes through a series of islands in the Caribbean. Behind some bushes, people are wet, fearful, and maybe disoriented. In that state they will leave, forget, surrender, dispose or lose objects, clothes, letters, products or photos. These objects are the source of an archive that we have created.

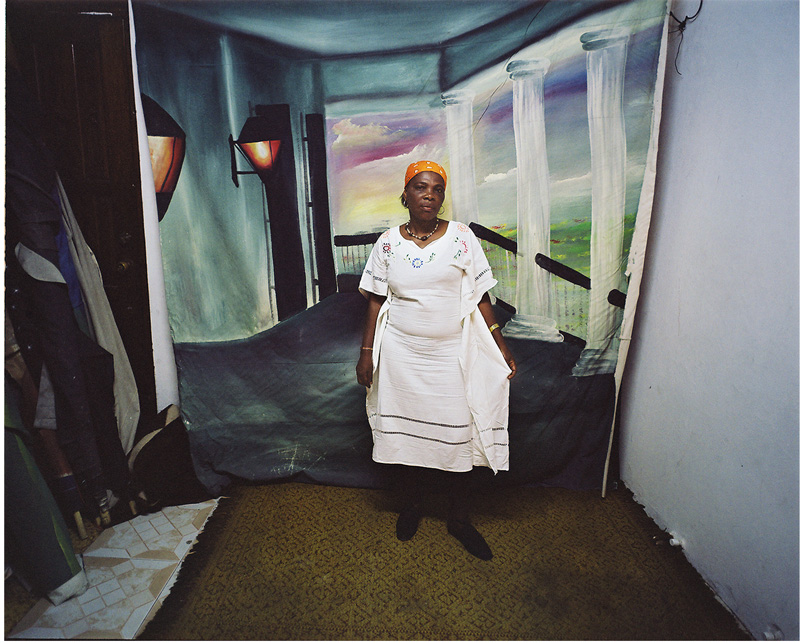

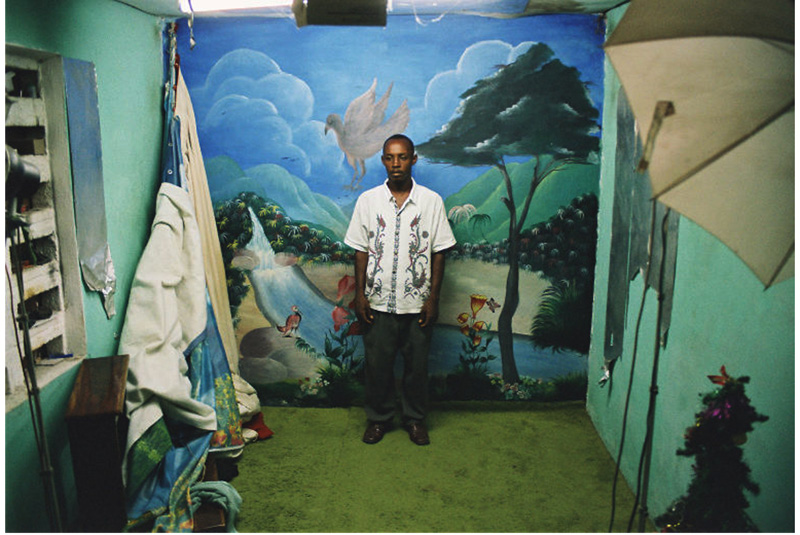

The proposed show deals with Haitian migration based on studio photograph portraits found near the shore or the woods of the US Virgin Islands, specifically on the small island of St. John, where they are thrown aside by the owners while they are running from the migration police. These photographs become physical witnesses as they become transmogrified (distorted and transformed) by the effects of water and they become symbolic witnesses of their identity or others’ identity in transformation.

The images are classic portraits taken in photography studios found in Haiti, these studios were almost immediately introduced in Haiti by the French colonial power upon invention in France, and the photographic portrait became a massive expression of self-identity. Painted backgrounds then evolved from realistic scenes to naïf painting depicting ideal landscapes, imaginary constructions of the cities in the Diaspora, and Utopic scenes. An example is the background that depicts a snow scene, this is a direct result of an imagined scene based on the photographs that family members send to Haiti, portraying them in a snow scene in Canada or New York.

In that context we understand the photo studio performance as the initiative journey, as the denial of chaotic reality and the active self-construction of their own imaginary and Utopic ideal. The act of the portrait ultimately becomes simultaneously an act of memory, leaving the resulting images to others to remember him or her and imagine his/her future, through this desire of a journey to the landscape painted as background. Ultimately the photographs are an act of resistance, where people take control over there own construction of their identities.

The proof of these journeys of transformation is these photos found in the woods and shores of USVI. These images are an index of the journey: the photos are subjected to the migration process, the transformation of the elements—salt water, exposure to the sun and rain—as a metaphor of the transformation of identity, and the psychological effects of the journey.

Language Book page (fig.001)

The article BDB::BP::004, is a page taken from a French – English language book. This particular page describes a conversation inside a train—a romanticized version of a trip in a fantasized place far different than the locus of migration.

We believe the immigrant imagined his journey in part as the page describes, and it also provided a mental landscape to map out what he encountered. The dialogue on that train, described on the dictionary page, is a dream. It is the active imaginary of another possible landscape—one of many potential alternatives.

The backpack contains a letter from Ulysses to his brother. That letter describes the language book Ulysses purchased to learn English. He added that he would send the dictionary to his brother before he embarked to the USA, so his brother could learn English and to later join him in the USA.

The “Tchala” (fig.002)

The “Tchala” is a fragile book with over 200 stapled pages, easily found on the streets of Haiti. Inside you will find in alphabetical order, numerological translations of dreams. For example:

dream of travel in an airplane……………03…29.

The “Tchala” provides concrete realism to the dream. The dream then becomes transformative. The dream is the basic unit to initiate change. Practitioners of vodou believe in the significance of dreams to plan a course of action to resolve problems. The purpose of this book is to use the numbers based on a dream from the night before to play the lottery. In Haiti there is a network of places to play the lottery. They are easily identified because they have the sign “Bank” and are known by the Haitian people as “Bank Borlette”. These borlettes originated during the dictatorship of Francois Duvalier. Duvalier legalized the lottery soon after it was initiated in 1969. It is estimated that Port au Prince is now home to nearly 2,000 borlettes. These institutions are the interstices between dreams and economics.

Photo studios in Jacmel Haiti.

These photographs become physical witnesses because they become transmogrified images, distorted and transformed by the effects of the water over the emulsion, or they become symbolic witnesses of their identity or others identity in transformation.

For this installation we choose to focus specifically on some images left by Haitians and Dominicans upon arrival to St. John that were thrown aside by the owners while they were running from the migration police.

The images are classic portraits taken in photography studios found in Haiti. Painted backgrounds depict ideal landscapes, imaginary constructions of the cities in the Diaspora, and utopic scenes.

In that context we understand the photo studio performance as the initiative journey, as the denial of chaotic reality and the active self construction of their own imaginary and utopic ideals. The act of the portrait ultimately becomes simultaneously an act of memory, leaving the resulting images to others to remember him or her and his/her future, through this desire of a journey to the landscape painted as background.

The prints (24” x 36”) are photos found in the USVI. The installation works in relation to the trip/journey of the migrant. The studio photos (stills from video) represents the vision of a new landscape, portrayed by the painted background, the beginning of the journey and the construction of a memory, a fictional new geography that exists somewhere in the future.

Next is the journey told by the whiteness (described in the video of the map), where the story focuses on the memory of the journey, the embedded process of motion between islands, the journey that transforms memories and images.

The proof of this journey of transformation are these photos found in the woods and shores of USVI. These images are an index of the journey: the photos are subjected to the migration process, the transformation of the elements--salt water, exposure to the sun and rain--as a metaphor of the transformation of identity, and the psychological effects of the journey.